- Home

- Mackenzi Lee

The Gentleman's Guide to Vice and Virtue Page 2

The Gentleman's Guide to Vice and Virtue Read online

Page 2

“I need a private word with Henry.” He nods at Percy’s aunt and uncle with hardly a glance—proper salutations aren’t for lower members of the peerage.

“The boys are leaving today,” Mother tries again.

“I know that. Why else would I wish to speak to Henry?” He lobs a frown in my direction. “Now, if you don’t mind.”

I toss my napkin onto the table and follow him from the room. As I pass Percy, he looks up at me and his mouth curls into a sympathetic smile. The faint freckles he’s got splattered below his eyes twist up. I give him an affectionate flick on the back of the head as I go by.

I follow my father into his sitting room. The windows are thrown open, lace drapes casting lattice shadows over the floor and the sickly perfume of spring blossoms dying on the vine blowing in from the yard. Father sits down at his desk and shuffles through the papers stacked there. For a moment, I think he’s going to start back in on his work and leave me to sit and stare at him like an imbecile. I take a calculated risk and reach for the brandy on the sideboard, but Father says, “Henry,” and I stop.

“Yes, sir.”

“Do you remember Mr. Lockwood?”

I look up and realize there’s a scholarly swell already standing beside the fire. He’s redheaded and ruddy cheeked, with a patchy beard decorating his chin. I had been so intent on my father, I’d failed to notice him.

Mr. Lockwood gives me a short bow, spectacles slipping down his nose. “My lord. I’m sure we’ll become better acquainted in the coming months, as we travel together.”

I’d like to throw up on his buckled shoes, but I refrain. I hadn’t wanted a bear-leader, primarily because I’m not interested in any of the scholarly things a bear-leader is meant to teach his charges. But a guardian presence of their selection had been one of my parents’ conditions for my touring, and as I had very few chips to wager in that game, I had agreed.

Father laces the papers he was mucking with into a leather skin and extends it to Lockwood. “Preliminary documents. Passports, letters of credit, bills of health, introductions to my acquaintances in France.” Lockwood tucks the papers into his coat, and Father twists around to face me, one elbow resting on his desk. I slide my hands between my legs and the sofa.

“Sit up straight,” he snaps. “You’re small enough without slumping.”

With more effort than it should take, I pull back my shoulders and look him in the eye. He frowns, and I nearly sink straight back down.

“What do you think I wish to speak about, Henry?” he says.

“I don’t know, sir.”

“Well, take a guess.” I look down, which I know is a mistake but I can’t help it. “Look at me when I’m speaking to you.”

I raise my eyes, staring at a spot over his head so I don’t have to look straight at him. “Did you want to discuss my Tour?”

He rolls his eyes, a short flick skyward that’s just long enough to make me feel like a bleeding simpleton, and my temper flares—why ask such an obvious question if he was just going to mock me when I answered?—but I keep silent. A lecture is gathering in the air like a thunderstorm.

“I want to be certain you’re clear on the conditions of this Tour before you depart,” he says. “I still believe your mother and I are foolish to indulge you a single inch further than we already have since your expulsion from Eton. But, against my better judgment, I am giving you this one year to get ahold of yourself. Do you understand me?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Mr. Lockwood and I have discussed what we think is the best course of action for your time abroad.”

“Course of action?” I repeat, looking between them. Up until this moment, I’d thought we all understood that this year was for Percy and me to do as we pleased, with a bear-leader along to arrange the annoying things like lodging and food and provide an obligatory parental eye that, like any good parental eye, would be frequently blind to youthful iniquities.

Mr. Lockwood clears his throat rather grandly, stepping into the light from the window, then back out at once, blinking the sun from his eyes. “Your father and I have discussed your situation and determined that you will be best served with some restraints placed upon your activities while on the Continent.”

I look between him and my father, like one of them will crack and confess this is a jest, because restraints were certainly not part of the understanding I came to with my parents when this Tour was first agreed upon.

“Under my watch,” Lockwood says, “there will be no gambling, limited tobacco, and absolutely no cigars.”

Well, this is turning a bit not good.

“No visitations to any dens of iniquity,” he goes on, “or sordid establishments of any kind. No caterwauling, no inappropriate relations with the opposite sex. No fornication. No slothfulness, or excessive sleeping late.”

It’s beginning to feel like he’s shuffling his way through the seven deadly sins, in ascending order of my favorites.

“And,” he says, rust on the razor’s edge, “spirits in moderation only.”

I’m ready to protest loudly to this until I catch my father’s hard stare. “And I defer entirely to Mr. Lockwood’s judgment,” he says. “While you travel, he speaks for me.”

Which is exactly the last thing I need accompanying me to the Continent—a surrogate of my father.

“When you and I next see each other,” he continues, “I expect you to be sober and stable and”—he casts a look at Lockwood, like he’s unsure how to tactfully phrase this—“discreet, at the very least. Your ridiculous little cries for attention are to cease, and you’ll begin working at my side on the management of the estate and the peerage.”

I would rather have my eyes gouged out with sucket forks and fed back to me, but it seems best not to tell him so.

“I have set your itinerary with your father,” Lockwood says, withdrawing a small pad from his pocket and consulting it with a squint. “We begin in Paris for the summer—”

“I have some colleagues I’d like you to call on there,” Father interrupts. “Acquaintances it will be important for you to maintain once you’re over the estate. And I’ve arranged for you to accompany our friend Lord Ambassador Robert Worthington and his wife to a ball at Versailles. You will not embarrass me.”

“When have I ever embarrassed you?” I murmur.

As soon as I say it, I can feel us both riffle through our mental libraries for each incident in which I shamed my father. It’s an extensive catalogue. Neither of us says any of it aloud, though. Not with Mr. Lockwood here.

Lockwood chooses to take a clumsy hack through the awkward silence by pretending it doesn’t exist. “From Paris, we continue on to Marseilles, where we will deliver your sister, Miss Montague, for school. I have accommodation arranged as far as there. We will winter in Italy—I have suggested Venice, Florence, and Rome, and your father concurs—then either Geneva or Berlin, depending upon the snowfall in the Alps. On our return, we will collect your sister, and the two of you will be home for the summer. Mr. Newton will make his own way to Holland for school.”

The air in the room is hot, and it’s making me feel petulant. Or perhaps I’m entitled to a little petulance because this whole lecture seems a bit of a sour send-off and I’m still rather panicked over the fact that at the end of all this, Percy’s going to bloody law school in bloody Holland and I’m going to be properly apart from him for the first time in my life.

But then Father gives me a frostbitten look, and I drop my gaze. “Fine.”

“Excuse me?”

“Yes, sir.”

Father stares hard at me, his hands folded before him. For a moment, none of us speaks. Outside on the drive, one of the footmen scolds a groom to step lively. A mare nickers.

“Mr. Lockwood,” Father says, “may I have a moment alone with my son?”

As one, my muscles all clench in anticipation.

On his way to the door, Mr. Lockwood pauses at my side and gives me a short

clap on the shoulder that’s so firm it makes me start. I was expecting a swing to come from entirely the opposite direction and be significantly less friendly. “We’re going to have an excellent time, my lord,” he says. “You will hear poetry and symphonies and see the finest treasures the world has to offer. It will be a cultural experience that will shape the remainder of your life.”

Dear. Lord. Fortune has well and truly vomited down my front in the form of Mr. Lockwood.

As Lockwood closes the door, Father reaches toward me and I flinch, but he’s only going for the brandy on the sideboard, moving it out of my grasp. God, I’ve got to get my head on straight.

“This is the last chance I’m giving you, Henry,” he says, a bit of the old French accent peeping through, as it always does when his temper is rising. Those soft edges on his vowels are usually my first warning, and I almost put my hands up preemptively. “When you return home, we’ll start in on the estate work. Together. You’ll come to London with me and observe the duties of a lord there. And if you can’t return to us mature enough for that, then don’t come back at all. There’ll be no place left for you in this family or any of our finances. You’ll be out.”

Right on schedule, the disinheritance rears its ugly head. But after years of holding it over me—clean up, sober up, stop letting lads climb in through your bedroom window at night or else—for the first time, we both know he means it. Because until a few months ago, if it wasn’t me who got the estate, he’d have had no one to pass it to that would keep it in the family.

Upstairs, the Goblin begins to wail.

“Indicate that you understand me, Henry,” Father snaps, and I force myself to meet his eyes again.

“Yes, sir. I understand you.”

He lets loose a long sigh, paired with the thin-lipped disappointment of a man who’s just seen the unrecognizable results of a commissioned portrait of himself. “I hope you one day have a son that’s as much of a leech as you are. Now, you’ve a coach waiting.”

I fly to my feet, ready to be rid of this sweltering room. But before I get far, he calls, “One final thing.” I turn back with the hope we might speak from a distance, but he crooks a finger until I consent to return to his side. He casts a glance at the door, though Lockwood is long gone, then says to me in a low voice, “If I catch even a whiff of you mucking around with boys, while you’re away or once you return, you’ll be cut off. Permanently. No further conversation about it.”

And that is our farewell in its entirety.

Out of doors, the sun still feels like a personal affront. The air is steamy, a ferric storm beginning to conspire at the horizon. The hedges along our drive sparkle where the dew sits, leaves turned to the light and shivering when the wind runs through them. The gravel crunches as the horses paw at it, harnessed and anxious to depart.

Percy is already at the carriage, his back to the house, which allows me an unobserved moment of staring at his arse—not that it’s particularly noteworthy arse, but it’s Percy’s, which is what makes it very much worth the noting. He’s directing one of the porters loading the last of our luggage that wasn’t sent ahead. “I’ll keep it with me,” he’s saying, his arms extended.

“There’s room to stow it, sir.”

“I know. I’d rather have it with me is all.”

The porter surrenders and hands Percy his fiddle case, the only relic left him by his father, which he cuddles like he was concerned they’d never see each other again.

“Have your aunt and uncle gone?” I call as I cross the drive toward him and he looks up from stroking his fiddle case.

“Yes, we had a chaste farewell. What did your father want?”

“Oh, the usual. Told me not to break too many hearts.” I rub my temples. A headache is building to a boil behind my eyes. “Christ, it’s bright. Are we off soon?”

“There’s your mother and Felicity.” Percy nods in the direction of the front steps, where the pair of them are silhouetted against the white stone like they’re fashioned from cut paper. “You’d best say good-bye.”

“Kiss for good luck?”

I lean in, but Percy puts the fiddle case between us with a laugh. “Good try, Monty.”

Hard not to let that pinch.

Felicity is looking sour and unattractive as usual, with her face scrunched up against the sun. She’s got the bridge specs tucked down the front of her Brunswick—Mother might not have noticed, but I can see the imprint of the chain through the fabric. Barely five and ten and she already looks like a spinster.

“Please,” Mother is saying to her, though Felicity’s staring into the sun like she’s more interested in going blind than in taking maternal counsel. “I don’t want letters from the school about you.”

The finishing school has been a long time coming, but Felicity is still so scowly about it you’d think she hadn’t spent all her born days proving to my parents that if one of their children needed civilizing, it was she. Contrary thing that she is, she’s begged for an education for years, and now that it’s finally handed to her, she’s dug in her heels like a stubborn mule.

Mother opens her arms. “Felicity, come kiss me good-bye.”

“I’d rather not,” Felicity replies, and stalks down the steps toward the carriage.

My mother sighs through her nose, but lets her go. Then she turns to me. “You’ll write.”

“Of course.”

“Don’t drink too much.”

“Could I get an absolute value on too much?”

“Henry,” she says, the same sigh behind her voice as when Felicity stormed away. The what are we to do with you? sort.

“Right. Yes. I won’t.”

“Try to behave. And don’t torment Felicity.”

“Mother. I’m the victim. She torments me.”

“She’s fifteen.”

“The most vicious age.”

“Try to be a gentleman, Henry. Just try.” She kisses me on the cheek, then gives my arm a pat like she might a dog. Her skirts rasp against the stone as she turns back into the house and I go the opposite way down the drive, one hand rising to shield my face from the sun.

I swing myself into the carriage, and the footman shuts the door behind me. Percy’s got his fiddle case balanced on his knees and he’s playing with the latches. Felicity’s scrunched up in one corner, like she’s trying to get as far from us as possible. She’s already reading.

I slide into the seat beside Percy and pull my pipe from my coat.

Felicity executes an eye roll that must give her a spectacular view of the inside of her skull. “Please, brother, we haven’t even left the county, don’t smoke yet.”

“Nice to have you along, Felicity.” I clamp the pipe between my teeth and fish about in my pocket for the flint. “Remind me again where we’re permitted to drop you by the side of the road.”

“Keen to make more room in the carriage for your harem of boys?”

I scowl, and she tucks back into her novel, looking a bit smugger than before.

The coach door opens, and Mr. Lockwood clambers up beside Felicity, knocking his head on the frame as he goes. She slinks a little farther into the corner.

“Now, gentlemen. Lady.” He polishes his spectacles on the tails of his coat, replaces them, and offers us what I think is meant to be a smile, but he’s so toothy the effect is a bit like that of an embarrassed shark. “I believe we’re ready to depart.”

There’s a whistle from the footman, then the axles creak as the coach gives a sudden lurch forward. Percy catches himself on my knee.

And like that, we are off.

3

The great tragic love story of Percy and me is neither great nor truly a love story, and is tragic only for its single-sidedness. It is also not an epic monolith that has plagued me since boyhood, as might be expected. Rather, it is simply the tale of how two people can be important to each other their whole lives, and then, one morning, quite without meaning to, one of them wakes to find that i

mportance has been magnified into a sudden and intense desire to put his tongue in the other’s mouth.

A long, slow slide, then a sudden impact.

Though the story of Percy and me—the account sans love and tragedy—is forever. As far back as I can remember, Percy has been in my life. We’ve ridden and hunted and sunbathed and reveled together since we were barely old enough to walk, fought and made up and run amok across the countryside. We’ve shared all our firsts—first lost tooth, first broken bone, first school day, the first time we were ever sweet on a girl (though I have always been more vocal about and passionate in my infatuations than Percy). First time drunk, when we were reading at our parsonage’s Easter service but got foxed on nicked wine before. We were just sober enough to think we were subtle about it and just tipsy enough that we were likely as subtle as a symphony.

Even the first kiss I ever had, though disappointingly not with Percy, still involved him, in a roundabout way. I’d kissed Richard Peele at my father’s Christmas party the year I turned thirteen, and though I thought it was quite a fine kiss, as far as first ones go, he got cold feet about it and blabbed to his parents and the other Cheshire lads and everyone who would listen that I was perverted and had forced myself on him, which was untrue, for I would like it to be noted that I have never forced myself on anyone. (I’d also like it noted that every time since then that Richard Peele and I have had a shag, it’s always been at his volition. I am but a willing stander-by.) My father made me apologize to the Peeles, while he gave them the lots of boys mess around at that age speech—which he’s gotten a lot of use out of over the years, though the at that age part is becoming less and less relevant—then, after they’d left, he hit me so hard my vision went spotty.

So I had walked around for weeks wearing an ugly bruise and mottled shame, with everyone eyeing me sideways and making spiteful remarks within my earshot, and I began to feel certain I had turned all my friends against me for something I couldn’t help. But the next time the boys played billiards in town, Percy bashed Richard in the side of the face with his cue so hard that he lost a tooth. Percy apologized, like it was an accident, but it was fairly transparent vengeance. Percy had avenged me when no one else would look me in the eyes.

The Gentleman's Guide to Vice and Virtue

The Gentleman's Guide to Vice and Virtue This Monstrous Thing

This Monstrous Thing Loki

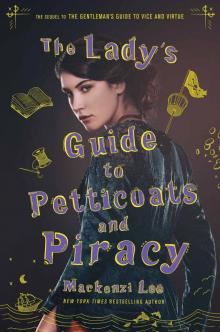

Loki The Lady's Guide to Petticoats and Piracy (Montague Siblings #2)

The Lady's Guide to Petticoats and Piracy (Montague Siblings #2) The Lady's Guide to Petticoats and Piracy

The Lady's Guide to Petticoats and Piracy