- Home

- Mackenzi Lee

This Monstrous Thing

This Monstrous Thing Read online

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

Advance Reader’s e-proof

courtesy of HarperCollins Publishers

This is an advance reader’s e-proof made from digital files of the uncorrected proofs. Readers are reminded that changes may be made prior to publication, including to the type, design, layout, or content, that are not reflected in this e-proof, and that this e-pub may not reflect the final edition. Any material to be quoted or excerpted in a review should be checked against the final published edition. Dates, prices, and manufacturing details are subject to change or cancellation without notice.

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

DEDICATION

FOR MOLLY AND HER AUTOCLAVE HEART

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

EPIGRAPH

Did I request thee, Maker, from my clay

To mould me Man, did I solicit thee

From darkness to promote me?

—John Milton, Paradise Lost, quoted in Frankenstein, or the Modern Prometheus by Mary Shelley

CONTENTS

Cover

Disclaimer

Title

Dedication

Epigraph

Chapter 1: Two Years Later

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Chapter 14

Chapter 15

Chapter 16

Chapter 17

Chapter 18

Author’s Note

Acknowledgments

About the Author

Copyright

About the Publisher

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

My brother’s heart was heavy in my hands.

The screws along the soldered edges flashed as the candlelight flickered, and I checked one last time to be certain the mainspring was fastened tight. It was smaller than I had imagined a heart would be, all those cogs locked together into a knot barely the size of my fist, but when I laid it in its place between the exposed gears in Oliver’s open chest, it fit precisely, the final piece of the puzzle of teeth and bolts I had been laboring over all night.

He wasn’t broken anymore. But he was still dead.

I slid forward onto my knees and let go a breath so deep it made my lungs ache. Below me, the inner workings of the clock tower hung still and silent. The gears had been unmoving for years, though tonight the pendulums swayed in the wind funneling from the jagged hole in the clock face. When I looked through it, I could follow the path the Rhone River cut across Geneva, past the city walls, and all the way to the lake, where the starlight was fading into milky dawn along the horizon.

When we dug up Oliver’s body, it had seemed fitting to bring him here, Dr. Geisler’s secret workshop in the clock tower where the resurrection work had begun, but now the whole thing felt stupid. And dangerous. I kept waiting for the police to swarm in—they’d kept a close watch on this place since Geisler’s arrest—or for someone to discover us, to walk in and spoil it all. I kept waiting for Oliver to sit up and open his eyes like nothing had happened. As though by simply being in this place I could reach out and pull his soul back from where it had landed when he’d crashed through the clock face and plunged.

“Alasdair.”

I looked up. Mary was kneeling on the other side of Oliver’s body, her face still spattered with cemetery dirt. We were a sight, the pair of us, Mary with her muddy dress and wild hair, me with the knees torn out of my trousers, braces unfastened, and my shirt smeared with blood. We looked mad, Mary and I, exactly the sort of people who would be digging up corpses and resurrecting them in a clock tower. I felt a bit mad in that moment.

Mary held out the pulse gloves and I took them, our fingers brushing for a heartbeat. She already had the plates charged, and when I pulled the laces tight around my wrists, I could feel their current thrumming inside me, soft and static like a second heartbeat that started in my hands.

“Alasdair.” She said my name again, so softly it sounded like a prayer. “Are you going to do it?”

I took a breath and closed my eyes.

When I remembered my brother, it would always be with his face bright and his gaze sharp. I would remember the days of being wild-haired boys together, of running in his shadow, of the hundred different ways he’d taught me to be brave and loyal and kind. Of falling asleep on his shoulder, and holding on to his sleeve in every strange new city. Of hunting with him in Lapland, skating the canals together in Amsterdam, watching him sneak away to visit the forbidden corners of Paris, and the nights he let me come along.

It would not be watching him take his last breath two nights before, already more corpse than man as he lay collapsed and bleeding in the velvet darkness on the banks of the Rhone.

I wouldn’t remember the night my brother died.

Instead, I would remember tonight, and what was about to happen, the moment hurtling toward me like a runaway carriage, when Oliver would open his eyes and look up at me. Alive, alive, alive again.

I knelt beside him and pressed my palms to either side of his shaved head, my fingers running along the track of stitches there. The metal plates beneath his skin were cold and tight. I closed my eyes as the shock of electricity leapt from my gloves, let it sing backward into my hands and all the way through me, and forward into Oliver, into his clockwork heart and his clockwork lungs and every piece of the clockwork that would bring him back.

There was a pulse, a flash, and the gears began to turn.

UNCORRECTED E-PROOF—NOT FOR SALE

HarperCollins Publishers

..................................................................

TWO YEARS LATER

The clockwork arm jumped on the workbench as the pulse from my gloves hit it.

I stepped backward to Father’s side, both of us watching the gears ease to life and intertwine. The ball joint in the wrist twitched, and Father’s eyes narrowed behind his spectacles. His fingers tapped out a quick rhythm on the top of the workbench that set my teeth on edge.

Finally, eyes still on the arm, he said, “You used the half-inch stock for the center wheel.”

It wasn’t a question, but I nodded.

“I told you to use the quarter.”

I thought about showing him the four quarter-inch gears I’d snapped the teeth off of trying to follow his directions before I had gone with my gut and used the half-inch, but instead I simply said, “It didn’t work.”

“Half-inch is too wide. If it slides off the track—”

“It won’t.”

“If it slides off the track—” he repeated, louder this time, but I interrupted again.

“The ratio wheel’s running fine on half. The problem is that the ratchet’s catching on the—”

“If you don’t do the work the way I ask, Alasdair, you can stand out front and mind the counter instead.”

I shut my mouth and started putting my spanners back in their sling.

Father crossed his arms and glared at me over the workbench. He was tall and thin, with a boy’s frame that he’d passed on to me. I kept hoping I’d bulk up a bit, grow lean and toned like Oliver had been, but so far I was just skinny. Father looked dead harmless, with his tiny spectacles and receding hairline. Not the sort of man you’d expect to be illegally forging clockwork pieces to human flesh in the back of his toy shop. Some of the other Shadow Boys we’d met looked the part, with scars and tattoos and that sort of shady, underground air about them, but not Father. He looked, more than anything, like a toy maker. “Morand’s coming for this tomorrow before he leaves Geneva,” he said, tapping one finger against the clockwork arm. The pulse had been so small that the gears were already starting to slow. “There isn’t time for trouble with it.”

“There won’t be.” I dropped the sling of spanners into my bag, careful to avoid the stack of books nestled in the bottom, and turned to meet his frown. “Can I go now?”

“Where are you rushing off to?”

I swallowed hard to push back the dread that bubbled up inside me when I thought of it, but I had put it off for the last three days—longer than I should have. “Does it matter?”

“Your mother and I need you home tonight.”

“Because of the Christmas market.”

“No. We need you for . . .” He pushed his spectacles onto his forehead and pinched the bridge of his nose. “Because of what day it is.”

My hand tightened on the strap of my bag. “You thought I forgot?”

“I didn’t say that.”

“How could I forget that today’s—”

He cut me off with a sigh, the weary, heavy sort I’d heard him use so many times on Oliver but now belonged just to me. I know, I wanted to say, your older son was a disappointment, and now your younger son is even worse. But I kept my mouth shut. “Just be home on time tonight, please, Alasdair. And put your coat on before you go out into the shop, you’ve got grease all over your front.”

“Thank you.” I swept the rest of my tools and the set of pulse gloves into my bag, then picked my way across the workshop toward the door. There were no windows, and the flickering shadows cast by the oil lamps made the room seem smaller and more cluttered than it was. My breakfast dishes from the morning were still stacked on the chair where clients usually sat, and my teacup had tipped over so the dregs soaked into the worn cushion. There were gears and bolts everywhere, and a layer of rusty shavings coated the floor like bloody snow.

“French in the shop,” Father called to me as I pulled my coat on.

“I know.”

“No English. You sound more Scottish than you think, especially when you and your mother get going. Anyone could overhear you.”

“Sorry. Désolé.” I paused for a moment in the doorway, waiting for the rest of the lecture, but he seemed finished. He was still staring at that damn center wheel with his hands folded, and I wondered if he’d switch it out while I was gone. He’d get a pinched finger if he tried, and it’d serve him right for doubting me. I turned and headed down the short corridor that led to the shop.

The workshop door couldn’t be opened from inside—Father had rigged up that precaution after Oliver opened the hidden door in our shop in Amsterdam when there were nonmechanical customers out front. I gave a light tap and waited. There was a pause, then a woosh of air as the door chugged open.

After all morning shut up in the workshop, the winter sunlight through the front windows nearly knocked me over, and I had to blink hard a few times before the toys lining the walls came into proper focus. “Come in quick,” Mum said, and I stepped past her as she threw her shoulder against the door and it eased back into place with a piston hiss, leaving the wall behind the counter looking again like a shelf stacked with dollhouse furniture.

Mum wiped her hands off on her apron, leaving a smear of plaster dust from the door, then looked me up and down. She was dark haired, same as I was, and thin as my father, but I could remember a time when she hadn’t been. The last few years had carved her out. “Goggles,” she said, pointing to the magnifying lenses slung around my neck. As I shoved them under my shirt collar, she added, “And you’ve got grease on your face.”

“Where?”

“Sort of ”—she gestured in a circle with her hand—“everywhere.”

I scrubbed my sleeve across my cheeks. “Better?”

“It’ll do until you wash up properly. Did you get Morand’s arm finished?”

“Yes.” I decided not to mention the spat over the center wheel. “Don’t let Father hear you speaking English.”

“Is he in one of his moods about it?”

“Isn’t he usually?” I did my best imitation of Father. “Nous sommes Genevois. Nous parlons français.”

She picked up the interior of a gutted music box and the set of jeweler’s pliers beside it. “Well, he can say it all he wants, doesn’t change the fact we aren’t Swiss, same as we weren’t French when we lived in Paris.”

“Or Dutch in Amsterdam,” I added, adjusting the strap of my bag as I turned.

“Hold up, where are you going? I’ve got something for you.”

I stopped halfway to the door. “Just an errand.”

“This late? It’s nearly supper.”

“It’s for the Christmas market,” I lied, then added quickly, “What have you got for me?”

She fished a wrapped package from the mess strewn across the counter and held it up. “It came this morning.”

I’d never gotten a letter in my life, let alone a package, and I took it curiously. There was a London port-of-origin stamp in one corner, and across the front was my name in thick, loopy handwriting that caught me under the chin and zapped me like an electric shock from the pulse gloves. “Bleeding hell.”

Mum frowned. “Don’t cuss.”

“Sorry.”

She poked hard at the pin drum with the tip of her pliers. “How’d I end up with two boys who cussed like sailors? We didn’t teach you that.”

I held up the package so she could see the front. “It’s from Mary Godwin. Do you remember her?”

“That English girl who hung about you and Oliver the summer before—” She stopped very suddenly and our gazes broke apart. I looked down at the package, but that made my heart lurch, so I looked back up at Mum. She was staring at the music box, her fingers running a slow lap around its edges. “Everything happened that year, didn’t it?” she said with a sad smile.

It was such an understatement I almost laughed. 1816 had been the year that cleaved my life into two jagged halves, the before and the after—before Mary had come and gone, before Geisler had been arrested and then escaped Geneva, before Oliver had died.

Mum twitched her pliers in the direction of Mary’s package. “What do you think she wants?”

I didn’t have a clue. I couldn’t imagine Mary would stick any of the unsaid things between us in a letter and drop it in the post after a two-year silence. “Probably just a catch-up,” I said lamely. “You know, how are you, I miss you, that sort of thing.”

I miss you.

I checked my heart before it ran away with that one.

Streets over, the bells from Saint Pierre Cathedral started chiming four. I should have been long gone by now, I realized with a jolt. I dropped Mary’s package into my bag, then started for the door again. “I’ve got to go, I’ll see you later.”

“Be back for supper,” Mum called.

“Yes.”

“You know what day it is.”

The inverted shadow of our name painted on the glass—FINCH AND SONS, TOY MAKERS—fell at my feet as I turned the knob. “I’ll be back,” I said, and shoved my shoulder into the door.

A gasp of December air slapped hard enough that I pulled my coat collar up around my jaw. The sun was starting to sink into the foothills, and the golden light winking off the muddy snow and

copper rooftops was so bright I had to squint. A carriage clattered across the cobblestones, the clop of horses’ hooves replaced by the mechanical chatter of the gears. I got a faceful of steam as it passed.

I didn’t have money for an omnibus ticket, but I was running late and the books bouncing around in my bag made it heavier than I was used to. It was a good bet no one would be checking tickets today. When the police force had redoubled their efforts at exposing unregistered clockwork men in the autumn, things like free riders on the omnibus had slipped down their list of concerns.

I crossed the square and joined the crowds spilling toward the main streets that led to financial district and the lake beyond it. On the stoop in front of Hôtel de Ville, a beggar was sitting with his head bowed and a tin cup extended. One of his sleeves hung empty, but the arm shaking his cup was made of tarnished clockwork, the leather gauntlet that covered the gears starting to feather with wear. Three boys in school uniforms sprinted by, and one spit at him as they passed. I looked away, though, and without meaning to, I started thinking about how I’d fix that rusted arm if he came into our shop. He needed thinner fingers with smaller gears, a hinge pin at the wrist—I would have added that to Morand’s arm if I’d thought Father would let me get away with it.

The omnibus was already at the station when I arrived, and I found a spot to stand beside the door, close enough that I could bolt if a policeman got on to check tickets. As the omnibus pulled away from the curb with a pneumatic growl, I retrieved Mary’s package from my bag and stared again at my name in her perfect handwriting across the front. Somehow it felt strange and familiar at the same time. I slid my finger under the seal and tore the wrapping off.

It was a book, green and slim, with the title printed in spindly gold leaf on the spine: Frankenstein, or The Modern Prometheus.

I didn’t have a clue what a Frankenstein was, or a Prometheus. I thought for a moment it was some of the daft poetry she and Oliver had spent all summer obsessed with, but there wasn’t an author’s name on the binding—not Coleridge or Milton or any of the others they obsessed over. I flipped through the first pages, then back to the spine to be certain I hadn’t missed it, but there was only the odd title.

The Gentleman's Guide to Vice and Virtue

The Gentleman's Guide to Vice and Virtue This Monstrous Thing

This Monstrous Thing Loki

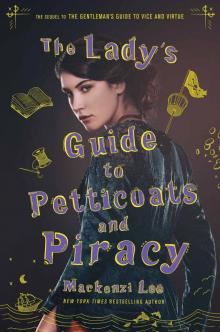

Loki The Lady's Guide to Petticoats and Piracy (Montague Siblings #2)

The Lady's Guide to Petticoats and Piracy (Montague Siblings #2) The Lady's Guide to Petticoats and Piracy

The Lady's Guide to Petticoats and Piracy